On forgiveness

a short story about wildflowers and loss

The creek that day was warm enough to feel your toes, but cold enough to make you yelp if you dunked your plumbs. I knew the bass would be spawning soon, so I drifted crayfish patterns under Boogle Bugs and picked apart the bittersweet water on my way upstream. The winter storms that year were the worst in a while, so there was plenty of new structure to navigate. With one eye on my line, my other wandered, searching for a familiar sign among all the new neighbors. A hawthorn poked me in the shoulder, warning me to watch my back cast. A moccasin basked on a mountain laurel branch, both naked. Wisteria mocked azalea as it hogged all the bumble bees in the tree canopy. I was eager to take it all in, but hopeful to find one treasure in particular that I knew would reassure me that spring time was really here. Atamasco Lily.

A freshly fallen tulip tree had slowed the rushing water enough to make a nice little sand flat that was covered in fish. I caught several nice bass and sunfish, and watched a few gar roll around in the sprouting water willow. I thought about how in a few weeks that tulip tree would probably be gone, with nothing but chainsaw scars in the stump to remember it by. Years of education in ecology had made me a pessimist. I ducked under the fallen branches where the water was deeper, and let out a pathetic yelp. The lilies wouldn’t be much farther upstream, and I was so looking forward to visiting with them.

As I waded up past the dog leg pool to the gently sloped banks where I had come for years to pray, I noticed a horrible change. The property had been developed since my last visit, and the trees that once shaded this pool had been mulched. The rich riparian soil that should have been decorated with lilies was now covered in rip rap to prevent the inevitable shear and erosion of future floods. I scaled the bank, searching desperately for those delicate white flowers. I cursed and gnashed my teeth as I searched, boiling with anger. My sanctuary was razed by these hideous, greedy vandals who couldn’t see the water from their outdoor kitchen with a flatscreen TV. These new neighbors were not welcome.

The blanket of blooms that I yearned for all winter long was reduced to one flower, choking in the mulch. I cried ugly angry tears. I called Alex. I had kept this place secret to protect the solitude that made it so special, but I needed somebody to know what I had lost. I wanted someone to hear my mourning.

Just a few months earlier, Alex’s family nearly lost their own sanctuary. An arsenist burned the church she grew up in, causing millions of dollars of fire and smoke damage. I joined them for Easter service, and we winced at the blackened walls covered with tarps. The new pastor’s sermon was slightly scornful, but ended with forgiveness. Today, the church is mostly restored, and I have hope that the lilies will come back once I convince the landowners to replant their riparian zone. But first I need to forgive them, which is not something I would have ever considered had I not fallen in love with the grace of my fiancée and her beautiful Christian family.

Trip Reports: Vol. 4, by Guest Author: Ryan Gary

“Arriving at a set up camp on the cusp of a weeklong trip is the confluence of optimism and exuberance, where nostalgia lives.”

There’s no easy way to get to the small corrugated tin camp at the end of the Mississippi River, but this trip I made it particularly hard on myself. Sixteen hours of driving, Baltimore to Mobile, to pick up my friend Broom. I crashed at his place, and in the morning, we left for camp stopping for the necessities along the way. “If there’s not a single box of number two steel shot off of I-10 from here to New Orleans there’s a bigger issue going on”, said in confidence within the first fifteen minutes of the drive. There was apparently a much bigger issue going on. Doubling down on groceries and beer is the only way to smooth over showing up to a five day duck hunting trip with a single box of shotgun shells.

The road trip ended in Venice, Louisiana, mostly because there was no more road to drive on. The last leg to camp was South Louisiana’s version of a backpacking trip: gas-powered, pack-it-in, pack-it-out. It’s an eleven-mile boat ride from the ramp to the canal just after the Head of Passes, where the river breaks into a delta, a sketchy course to charter even in favorable conditions. It had been five years since my last trip downriver, but I was greeted at camp just as every other time: a variety of yells, screams and waving arms behind the screened in porch as we idled down the canal to the dock. Arriving at a set up camp on the cusp of a weeklong trip is the confluence of optimism and exuberance, where nostalgia lives.

The tin camp is situated on top of an L-shaped levee only a couple hundred yards from the Gulf of Mexico. It’s one of two dozen camps, stacked close enough together that you can toss your neighbor a beer if they’re sitting on the front porch. I’ve never gotten the full story of how one stumbles into the upkeep or owning of one of these camps, but I do know if you look at satellite imagery of the canal, they started showing up sometime between 1998 and 2006. Our camp an old houseboat that Hurricane Katrina pushed up on to the levee. You’d only know if someone pointed out the fiberglass floors or you went to grab the pirogues from underneath and saw the aluminum pontoon logs that used to float it.

The camp entrance is on the starboard side, facing the canal. Inside is one main room. Sleeping arrangements three bunkbeds and a couch, just enough for the seven guys and five dogs this week. The door on the right is the bathroom and shower, on the bow. The stern is dedicated to conversation and consumption. A white folding table surrounded by old chairs, where you procrastinate the morning hunt or eat dinner off of paper plates. A small table along the back wall for phone chargers, coffee makers and whiskey. The necessities. Cabinets, a stove, and a sink line the port-side wall under a window where you can watch Grey Ducks pile in to the pond behind the levee while you’re doing the dishes. I’ve been assured the juice is not worth the squeeze.

The hunting over the next few days was what I’ve come to expect of this part of the country: we’d work for them, but there would be opportunities. There’s never a shortage of teal, but they don’t decoy like the Grey Ducks or Pintails. The first two mornings would be filled with the teal birds and a handful of Do Gris (what anyone south of I-10 calls a Scaup). Enough to scratch my itch and give the dogs work, but after three days of below freezing temperatures it was disappointing to the boys who had been hunting out of the tin camp for close to two decades.

A lull always starts talk about how ducks just don’t come down to South Louisiana anymore. “Before Katrina the sky would be black with ducks, every single pond that we’d check would be full after a front like this”, something I hear almost every trip to the tin camp.

Chris, who spends the most time there, ran me up one of his canals on the afternoon of the third day to a pond called Bally’s Grey Duck Hole. Named after his all but retired yellow lab. On the way out, there were unfamiliar gaps in the Roseau Cane on the left and right. In some places, it ended abruptly, in ways I didn’t remember from previous trips. It had been years, but I was almost certain there should have been cane there to define those shallow edges of the canals before you could turn. Without natural channel markers, experience is what kept you from sticking a boat in the mud.

On the fourth day, a front was in the forecast: not cold but a windy, rainy, nasty front - the type of front that excites a true duck hunter, adamant on conquering the elements. But after three days of average hunts and four nights of exceptional consumption and conversation at the white folding table, I wouldn’t put myself in that category.

Chris led the charge that morning with Joe, a new arrival determined to hunt at least once, and Broom, the Mobile product I picked up. Still relatively green in the field of duck hunting, Broom was not going to give the ducks a day off. With no evidence this hunt would be more exceptional than the previous, I was content to sleep in. When that happens though, the hunting is always good.

Those three would have one of my favorite types of mornings. Shootin ‘em in the slop, workin for ‘em, type-two fun. Not bad when you come back with a haul of Grey Ducks, Pintail and teal to a hot breakfast either. Broom certainly deserved it. A Venice Burner.

The rest of the camp energized by their limit of ducks set off to chase the same results in the afternoon. Emulating success we’d had in similar conditions, the goal was one last hunt scratching together every eligible gun left at the camp. A party hunt. Two boats placed nose to nose in a patch of Roseau Cane with two sacks of decoys in 45 degree angles going away from the boats. The same sloppy conditions as this morning persisting.

First came rolling groups of teal and Dos Gris on the edge of a 12 gauge’s range, not sold on committing to decoys in a 20 mph cross wind. We had enough of them anyway this week, no one mounted a gun. Interspersed were small, high groups of Grey Ducks, equally unsatisfied with the crosswind. “Not looking good Bob”. Just before the sky reached the moment of dimness when someone is provoked to question the remaining shooting time, big ducks rolled through the spread. A volley, then falling ducks. “Were those Canvasbacks??” comes from the other boat. For the next twenty minutes, we had our shot at the King of Ducks trying to find a home before sunset.

The five days we spent at the corrugated tin camp wouldn’t be defined by limits of ducks, but by the exercise of chasing ducks, and it’s always that way here. The canal off of Pass a Loutre is one of the few places I travel in the pursuit of game where success is judged by a different metric. It’s never the pile of birds or the ice to fish ratio in the cooler, although we do make a point to brag when either are favorable. Here, it’s about playing the game in a place that feels like you’re out on the edge of the world. The only reminders that there’s anything but duck hunting are the tanker ships going upriver and the helicopters flying out to the oil rigs. Over those five days we played the game, with dogs named Rouge, Art, Gin, Grass and Ace. Hunting out of pirogues and towing bateaus across the marsh in rain and wind. Rewarded with enough pretty ducks to be content with a long boat ride upriver and return to pavement.

If you’ve made it this far, please enjoy a coupon code for 15% off bait shop gear. DOSGRIS23

Trip Reports: Vol. 3, by Guest Author: Swanny Evans

Swanny Evans learns a thing or two about hunting over a squirrel dog from his friend and mentor, UGA legend David Osborn.

Avery Kelly & David Osborn with Dexter, the Cur.

Friday night, the weather was looking pretty dismal for bowhunting the next day. The warm drizzle that was predicted didn’t exactly have me excited to sit in a tree, and I didn’t want to have to race the rain to a blood trail if I happened to get lucky. I was debating whether to even set my alarm when I got a text from an old friend with a new-to-me idea. David Osborn was taking a student from UGA squirrel hunting with his Treeing Cur named Dexter in the morning and asked if I wanted to go. I just replied, “Yes” and set my alarm.

Let me take a quick step back to explain a few things before we dive into this trip report. I mentioned this idea was “new-to-me”, but I didn’t mean squirrel hunting. I am one of the seemingly dwindling population of lucky ones that was introduced to hunting at a young age and squirrel hunting was that first introduction. I remember my brother and me being knee-high to a grasshopper, tagging along with my dad on our first ever hunt. We were the dogs that day, as dad would yell, “Run around that side of the tree and scare ‘em back this way!” My brother and I would circle the tree, dad would shoot, and I can honestly say I was hooked from that point forward. I have hunted all sorts of game since then, but I don’t think a year has passed where I haven’t hunted squirrels. They are plentiful, taste great, and can be quite the challenge, so what’s not to love? The “new-to-me” part of this hunt was Dexter, the Treeing Cur. While I have been the squirrel dog in the past, I have never hunted over one.

My alarm went off at 5:30 AM the next day, I started the coffee, and packed my squirrel hunting paraphernalia while it was brewing. There are always a few staples that come to the woods with me when squirrel hunting. I typically bring an old-school game belt that my dad loaned me about 15 years ago (I clearly haven’t returned it), my game shears which also double as my kitchen scissors (I know, I am really embracing the bachelor life), and last but not least, I always take a gun. Now I usually default to a Savage Mark II 22lr that I have killed pretty much everything under the sun with including a few deer (don’t worry that was under a research permit; a story for another day), but every once in a while, when I am feeling nostalgic, I take a side-by-side Stevens 16 gauge that was passed down to me from my grandfather. Since I didn’t really know what to expect hunting over a dog, I packed both guns, filled up my coffee mug, and headed out the door.

We were planning to hunt a large piece of public land, but we were going to meet at Osborn’s house and ride together. I pulled in at about 6:45 AM and met Avery Kelly, an undergrad that volunteers with the UGA Deer Barn. Avery, much like me, had never hunted over a squirrel dog and was pretty excited. While Osborn, Avery, and I discussed the game plan, Dexter was bouncing off the walls of the dog box in the back of the truck and whining with excitement, he knew where we were going. I patted him on the head, gave him the obligatory, but fond, “Good boy” and we were on our way.

Osborn leashing his Cur.

Before we get to the hunt, I feel like I better give some background on my old friend. Osborn is a researcher with the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at UGA who, despite not having a PhD or being a professor, has positively impacted hundreds of students and may be an author on as many or more publications than the professors there. Any student that came through Warnell and interacted with him to any significant degree would tell you the same, but what many people don’t know is that Osborn used to be famous in a much different (and perhaps smaller) world. Up until about 15 years ago he competed in squirrel hunting competitions all over the Eastern United States. He literally wrote the book on squirrel hunting with dogs (seriously, there is a book: Squirrel Dog Basics: A Guide to Hunting Squirrels with Dogs). Despite knowing David for over a decade, I have never squirrel hunted with him. He got out of the game 15 years ago and suddenly caught the bug again recently when he bought Dexter. Alright, back to the trip report.

We were riding down the dirt road through the middle of one of Georgia’s public lands and Osborn directed me to pull off to the side saying, “This looks good right here.” We unloaded and I overheard Osborn asking Avery if he had enough shells. Avery responded, “I have 15, that should be plenty.” I heard Osborn chuckle, grab a few extra shells for Avery and put them in his vest. Since they both had shotguns, I decided to take the Savage.

I am used to slowly moving through the woods and sitting for extended periods of time when I squirrel hunt. Let’s just say, I am glad I was wearing trail runners that day because once Osborn pointed Dexter in a direction, there wasn’t a lot of downtime. Within just a few minutes Dexter had already covered about 800 yards to our 500 and he had one treed. We came up over the ridge to see Dexter with his paws up on a large pine barking straight up, Osborn sort of groaned and mumbled something about the perils of a pine tree. Apparently, finding the tree the squirrel is in is only half (maybe more like a quarter) of the battle. The next step is trying to find the squirrel in the tree and Osborn told us pines always make that difficult. Dexter got tied off, we peered up into the limbs of this tree, shook vines, and looked from different angles to no avail; that squirrel had played this game before. “Let’s go find another one,” Osborn said as he redirected Dexter.

Dexter took off and disappeared over the next ridge. It started to drizzle a little bit and, “I am glad I didn’t decide to…” was all I got out before we heard Dexter bark again. “Three hundred and sixty-four yards treed that way,” is all Osborn said as he looked at data from Dexter’s GPS collar and we took off at a fast pace to the West. I was the first to make it to the large white oak Dexter was on and as I approached, I caught a glimpse of the squirrel repositioning when he saw me. I braced on the edge of a small tree, squeezed the trigger, and knocked the squirrel right out of the fork he was attempting to hide in. Over the next four hours we covered a little over six and a half miles, Dexter treed 17 times, and we killed seven squirrels. Dexter was clearly better at this than us and let’s just say those extra shells Osborn brought came in handy.

Avery, Osborn, and Dexter crossing a swollen creek.

As we hoofed it back to the truck out of breath, Osborn looked at me, smiled, and said, “It’s a little different experience than the way you squirrel hunt isn’t it?” Different is one way to describe it. While I don’t think I will be abandoning still-hunting squirrels, I can promise you that won’t be my last time hunting over a dog. The hunt was fast-paced, social, and covered an incredible amount of ground. Avery and I both had an excellent time. We all recapped the hunt as Osborn demonstrated his squirrel cleaning technique which I loosely call the “shirt and pants method” on my tailgate.

Osborn doesn’t know it yet, but I am going to find a way to invite my Dad on the next hunt with Dexter. I figure if we have a real dog there, I will get to hunt too and won’t have to spend my time circling the tree until dad gets a shot. If you have made it this far in this trip report, I encourage all of you to get outside and chase some of those bushy-tailed rascals. Together, we can make squirrel hunting cool again, introduce a few new people to the outdoors, and eat some delicious all-natural protein in the process.

The author (left) with the McNeals and Alexandra’s Satilla Gobbler from last spring.

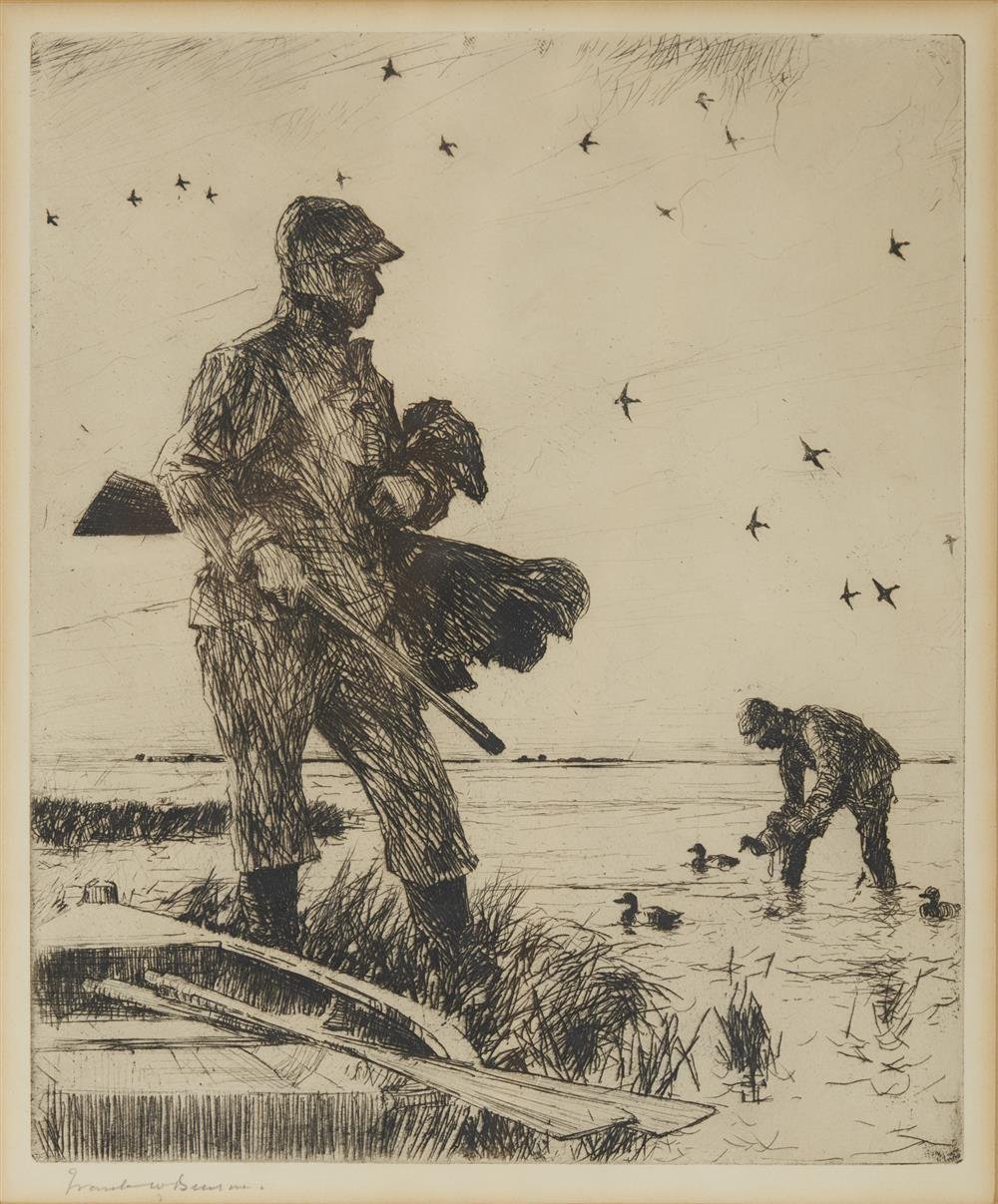

On Benson

One of the greatest sporting artists of his time.

This entry, the third in a series of art history posts, is a tribute to Frank Weston Benson, a truly great American artist (1862-1951). Benson was born in Massachusetts to a wealthy family from Salem. He studied art in Boston and Paris, and quickly became a well known portraitist and muralist. He was famous for his seaside portraits of his family on summer vacations in Maine, and the murals he painted for the Library of Congress.

Benson’s career is like the mirror image of Winslow Homer’s. Whereas Homer started off as a lithographer and illustrator and later moved to watercolors and oils, Benson became famous first for his Impressionist paintings, and then had a second, just as profitable career with etching. I’ve included a few of my favorite of his etchings, which mostly depict hunting scenes from his cabin in Cape Cod.

Winter Wildfowling, etching, 1927

Marsh Gunner 1925

One fun fact about Benson is that in the 1890s he joined a group called “The Ten”, which is probably the most badass group of artists in American history. “The Ten” broke away from the Society of American Artists because of their hostility to Impressionism which was making its way over from France. The group included the most famous American Impressionists of the time, and almost became “The Eleven”, except Winslow Homer turned down his invitation.

Duck Blind 1925

Running the Rapids 1927

My favorite thing about these works is the contrast. His use of negative space is genius, and the amount of detail he captures within even the darkest parts of the composition blows my mind. Notice the tiny highlights on the backlit figures. It turns them from anonymous silhouettes into characters with depth. Anyways, I hope you enjoy looking at these. I have them printed out at my office. Maybe someday I’ll find an original.

Deer Hunter 1924

Trip Reports: Vol. 2

Your mama has just tucked you in and given you a kiss goodnight. You hold the blanket over your head, knowing that as soon as she hits the light switch, your room will suddenly be crowded with a pack of starving gargoyles. Some nights you can ignore them and fall asleep quickly, but some nights you peek out and see a shadow move, or an unfamiliar reflection that you conclude must be the eyes of the biggest, slimiest monster you could possibly imagine, watching you in the dark.

You’re older now, and the dark isn’t so scary. Logic and reason have starved your childhood fears, and the shadows and glints in your bedroom can all be explained away. But I’m telling you, the glow-eyed gargoyles you thought you imagined are definitely real. And they live in Lake Seminole,.

It was darker outside than the farthest corner of my bedroom last Friday night. The night light hadn’t yet risen over the longleaf horizon so we motored out blind into the swampy lake. Three of us armed to the teeth, seeking vengeance against the gargoyles for all those sleepless childhood nights. Little did I know it would take all night, all day, and all night again to catch one.

Allen had scouted the area for weeks in advance of our trip. All season long he had been trying to fill his tag, first one he has had in years. This trip was all or nothing, so he called in the yanks.

Alex and I are novice hunters, but we are no strangers to boats, hooks, guns or hard work. Allen was relying on us to make the trip go smoothly and bring home the bacon.

We had a few opportunities on the first night. We lost count of eyeballs peering at us through the hyacinth blossoms. When the gap between a pair was wide enough, we’d shut off the trolling motor and coast up to them to make a cast with weighted treble hooks the size of a child’s hand. Despite our fairly precise casts, the hooks wouldn’t bite, and they glanced off the gargoyles’ scaly, scuted backs.

Just before dawn, we decided to go home and get some rest for the afternoon. As we unlocked the motel door, our neighbor came out and loaded his rods up in his bass boat.

“Good morning! Any luck?”

“Saw a few big ones, we’re gonna try again tomorrow. I mean later. Good luck fishing!”

“Good night!”

We got some winks and a burger and went back out around 11. We watched coots clumsily flop around the lily pads and gallinules hunt the hydrilla. Not much gargoyle activity besides one giant by an island we hadn’t hunted in the dark. We decided to go back and try for him that night.

At around 3, we drove back to base, turned on the Auburn game and took a quick nap. Taking a shower seemed futile, but the sleep was much needed. At dusk, we left again, this time determined to make it happen on the giant.

The coyotes were quiet on the second night, and the wind had laid down to give the hummingbird-sized mosquitos their chance at our rot-gut coffee-flavored blood. We swatted them away, begging the bats in our spotlights to work double time.

I missed a cast, and fumbled a hook set. Allen missed a cast. Alex missed a hook set. Then Allen found the giant. He made the right cast and heaved on him. In an instant the monster was under the boat, stuck in a cypress root ball. We didn’t stand a chance. He came off.

We were shocked at its power. I couldn’t believe how strong it was.. But we abandoned it to look for more opportunities. We missed some more, but never stopped hunting, never got discouraged. We had all night and no place to be.

Then the blood moon rose and the river came back to life.. We chased one towards the bank and missed the first cast. He popped back up 20 yards away. Cast again. Miss. Chase him away from the bank. Repeat. This one wanted to play the game. Alex and I each missed about 6 or 7 times. Accurately casting really heavy hooks in the dark as far as you can is hard! Get too close, and the predator slides away. Allen took the rod and made a perfect cast and came tight to it, the animal that could easily bankrupt every boat towing business in America if it could tie a knot: the American Alligator.

Allen fought it for 15 minutes, expertly avoiding entanglement with the trolling motor, steering us away from the bank the entire fight. I stood on the bow behind him to hold the spotlight and the harpoon, keeping the surface lit for my opportunity to stick it with the buoy line. Alex stood on the deck with his pistol and kept the buoy line from tangling around our ankles.

Allen tightened up to horse the giant, stiff body up off the bottom and the gator’s tail came to the surface. I quickly put down the spotlight so I could thrust with two hands. As soon as I slammed the point into its tail, all ten feet of that beast exploded in a wild fury. It snapped backwards and bit down hard on the harpoon handle. Crunch. The wood splintered and flew from my hands. I grabbed the rope and frantically held on as the gator dove back down and swam away, peeling drag on Allen’s line all the while.

I let it take some line but held on tight as we wrestled it back to the surface. Suddenly, Allen’s hook came loose and he dove for the other snagging line and threw it in. We both pulled as hard as we could, yelling for Alex to shoot him. As soon as his big head breached the water, I went deaf. Alex put two perfect shots in its head and suddenly it was all still. It was 1:30am.

I can’t imagine a more primal experience. Nothing else I’ve ever hunted could fight back. It was all a matter of finding it and shooting it. This game was completely different. To really experience the power of a game animal before you take its life is unique to alligator hunting. I don’t know if I’ll ever get the chance to go again, but I know I’ll never forget our trip. Or the weird cajun-seasoned dreams I had sleeping at a gas station in Eufaula on the way home. But that’s a story for another time. All that’s left is gratitude. to Allen, Alex, Big Jim, and most of all, this precious alligator that gave us such a great harvest.

On Pleissner

Poling Upriver, watercolor on paper 14.25 x 20.5 inches

This entry, the second in a series of art history posts, is a tribute and short bio of my favorite sporting artist of all time, Ogden Pleissner. I like him so much, I named my dog after him.

“You can say that a picture has a sense of place, but in a painting, a landscape, to me it’s the mood conveyed that counts.” -O.P.

Pleissner was born in Brooklyn, and had a fairly long career as an artist, beginning as a student at the Art Students League of New York, and ending with his death in 1983 in London, England. He taught at the Pratt Institute from 1930-1934, and the National Academy of Design from 1935-1937. During this time, he was somewhat of a fixture in the elite sporting world, which was mostly made up of rich carpetbaggers from New York and Boston who spent winters in the South Carolina low country, Florida, and the Caribbean. His sporting scenes depicted a pretty well established idiom of the time: hunters and anglers in spectacular landscapes.

Western Pheasant Hunting, watercolor on paper 18 x 28 inches

Pleissner loved the American west, having spent his adolescent summers in Wyoming with his family. As an adult, he enjoyed trips to the Adirondacks, Nova Scotia, and New England. His immense body of work covers everything from grouse and waterfowl hunting to salmon fishing. One common thread through his work is that the action is understated.

Grassing the Boat, watercolor on paper 16 x 20 inches

Pleissner’s sporting art to me is remarkable because of the contrast between his figure’s poses and the excitement of their sport. The sudden chaos of a pheasant bursting from the brush is somehow relaxing thanks to the softness of his portrayal. His subjects are usually posed in action, but also sometimes content to watch as the scene unfolds in front of them.

Salmon Fishing on the Miramichi, watercolor

His sporting scenes are romantic but accessible. He was a Realist after all. I especially connect to his paintings of canoe scenes, particularly the implied camaraderie between the subjects. These days when I’m on the river, I’m just as happy to watch a good friend fish as I am to fish myself.

Grouse Shooting, watercolor on paper, 16 x 28 inches

Fishing the George, watercolor on paper 16½ x 26½ inches

During World War II, Pleissner was enlisted in the U.S. Airforce as a captain in the Historical Division, stationed in the Aleutian Islands. He was commissioned to document the war efforts with paintings. He did most of his work in this period with watercolor, because it dried much quicker than oil paint in the wet Alaskan climate. He could be seen running in and out of his hut to dry a layer of paint by the fire before darting back into the elements to finish his work. Later in the war he was employed as a War Correspondent for Life Magazine in Europe where he painted a lot of scenes of urban life in France, Italy and Spain.

B-25 Bombers Over Aleutian Volcano, 1945

Pleissner is pretty much unanimously recognized as one of the gold standard painters of American sporting art. You can browse his work in a few collections online, and see some originals in galleries like the Sportsman’s Gallery in Charleston, SC. Look for more posts coming soon on some of the other founding fathers of this genre. I hope you learned something, and that this small contribution stokes a little bit of interest.

On observation, by Guest Author: Alexandra McNeal

“The attention and awareness we give to something has been proven to create time-based distortions.”

featured photo by Lawson Builder

photo by Lawson Builder

The anticipation of seeing the stuttering tip of a rod or hearing the zip of line peeling off a reel has always left me giddy with excitement. The adrenaline of hooking into a fish, no matter the technique or species, usually results in shaking hands and a racing heart. You might say I’m addicted to it. After that initial rush wears off, the contrast of those moments before and after the bite always stand out to me. Long moments of waiting and watching are suddenly punctuated by the chaos of landing the fish, removing the hook, taking a quick picture if desired, and getting the fish back in the water (or the cooler) as fast as possible. Sometimes, the moment comes and goes with such haste, I sit in the wake of the release a bit stunned as to what all just happened. I imagine the fish feels much the same way.

It’s so rare we get to interact with any marine life - outside of diving or an aquarium - and in the muddy waters of the lowcountry, hook and line are essentially the only way you can meet our aquatic brethren face to face. I try to make the most of those brief seconds and really observe the fish, taking in the minutia that is otherwise missed in the fray. The circlet of a red drum’s iris can be a mountain range of gold and amber, the blues in the tip of a tail can hint at what that fish has been dining on, and their rainbow of iridescence is something you can only see when the light hits their scales just so.

I’ve learned from this practice of conscious observation that you can actually make time slow down – and I’m not just talking metaphorically. If you’ve read or watched enough science fiction, underneath all the fantastical plots about space and time is a kernel of truth: that time is elastic and can be altered by things. One of those things is gravity. Time passes faster on top of a mountain than at sea level because the closer you are to a gravitational pull – the slower time moves. In addition to gravity, there are other things than can distort our perception of time. The attention and awareness we give to something has been proven to create time-based distortions. In short, the perceived duration of an event is lengthened when that event is subject to the full focus of our attention.

Now, I’m not saying you will create hours of extra time from being laser focused on a fish, but you can create a meaningful moment during an otherwise hurried experience. For all the enjoyment we get out of fishing, I think giving that animal our attention and our appreciation is the least we can do.

It's no secret that the skill of observing the natural world is something that our modern culture is no longer practiced in. Our attention is spread so thin, with screens vying for it at every turn, and when our food comes from the shelf instead of the forest, what need do we have to pay attention to animal signs or the fruiting of native plants? What was once second nature has now become something that we must be mindful of, lest we lose ourself between the digital world and the monotony of a domesticated routine.

To drive home my point, let me ask you, when is the last time you noticed a plant? I don’t mean just something green you passed by recently. When was the last time you noticed a plant enough to call it by its name?

The tendency of humans to no longer notice or differentiate the plants in their own environment has become such a pervasive issue that two botanists, Elisabeth Schussler and James Wandersee, coined the term “plant blindness” to describe it.

What does it matter if society has developed a blind spot for plants? There are actually quite a few unfortunate consequences that come from our lack of attention. Most conservation efforts tend to be concentrated on animals, particularly charismatic megafauna (elephants, lions, pandas, etc.), and plant research almost never receives the same amount of funding that animal focused projects do. Despite the fact that plants form the foundation of most food chains, are the source for countless live-saving medicines, and provide priceless ecosystem services, botany and horticulture programs at universities around the country have had to close their doors from lack of students and lack of money.

The heart of what I want to communicate here is that the practice of conscious observation inevitably cultivates gratitude and appreciation. By cultivating gratitude and appreciation, we begin to form a relationship with something – be it a fish, a plant, or an entire landscape. The people who interact with and form relationships with our resources are usually those who most resolutely protect it and, in today’s world, we desperately need more people developing relationships with flora, fauna, and places. People will fight for the things they love, but how can you love something if you don’t even know its name? Without encouraging public literacy of the natural world, we will slowly lose our best advocates to protect the land, educate future generations, and to speak up against development, pollution, or overharvest.

So, the next time you feel overwhelmed by the fleeting pace of life or think you don’t have time to stop and smell the roses, remember that you have a super power. You can choose to make time slow down. Even just a few seconds of your attention is enough to identify that wildflower, watch a spider spin its web, or look a redfish in the eye and see the multitudes they contain.

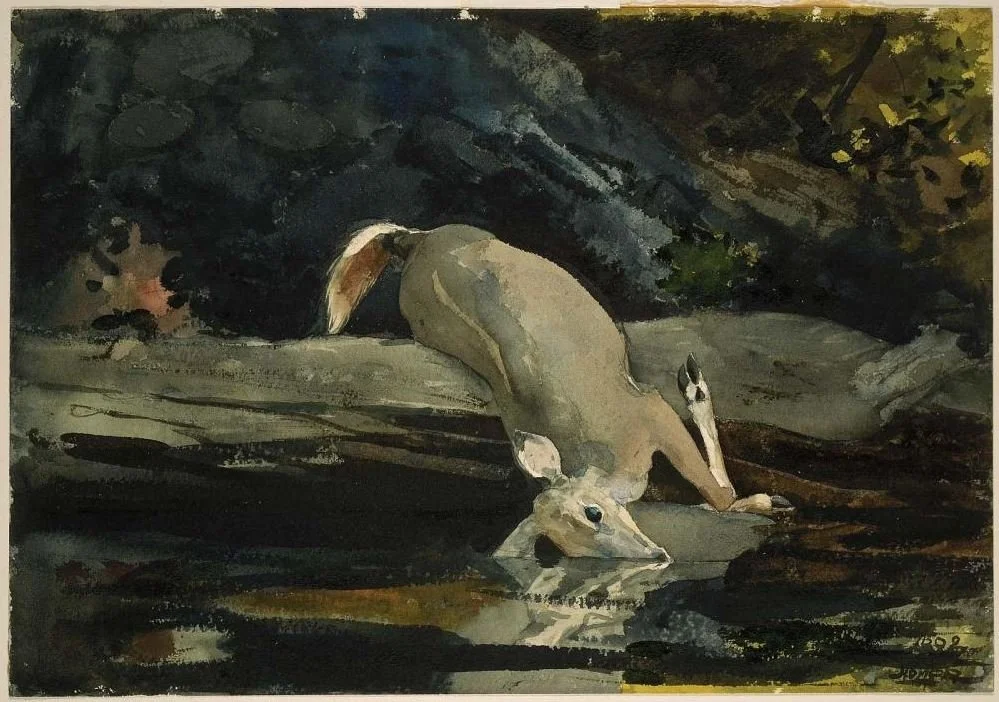

On Homer

A primer on Winslow Homer (1834-1910)

“End of the Portage” 1897

In an effort to promote the arts, and share some of my inspirations, I’ve decided to do a few short journal posts on art history. I’m not an expert, but I’ve done some research and developed an appetite for it. I consume art the same way I do just about everything in my life, with manic bursts of fixation and compulsive obsession. When I find a painter whose work I connect with, I dive into their portfolio and plaster my space with their work. One such painter whose work decorates the halls of my mind is Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

Homer is one of the founding fathers of traditional American sporting art: the depiction of hunters and anglers interacting with their landscape and quarry. Although his career started in lithography and illustration, Homer quickly rose to fame for his talents in oil painting and watercolor. He is still regarded as one of the best oil painters in American history. His interest in sporting pursuits arose from frequent fishing trips to the Adirondacks in upstate New York, which he enjoyed all his life.

“Shooting the Rapids” 1902

Homer’s watercolor sketches and paintings were revered for their unique combination of loose brush strokes and fine detail. He earned the nickname “the eye surgeon” for his ability to mark extremely fine details, often with a knife blade, to evoke emotional gestures from his subjects. I romanticize what life was like for Homer, hunting and trapping from canoes in Maine, fishing in Homosassa and the Keys, and frequent trips to Cuba. His most famous painting is probably “The Gulf Stream” which he painted shortly after the death of his father. He was deeply infatuated with the power of the ocean, and reflected often on the mortal relationship between humans and nature.

“The Fallen Deer” 1892

Homer’s depictions of hunting scenes were often meant to stir the viewer with uncomfortable and sometimes grotesquely posed game. Homer to this day is one of the few sporting artists who chose to show the unromantic side of hunting. He was sometimes frustrated with how his works were perceived, however, because he never meant to show cruelty, only the difficulty of taking a life. I’ve included a few of my favorite works here for your enjoyment, but I encourage you to peruse his larger body of work which is available in lots of different collections including the Metropolitan Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

“Homosassa River” 1904

On Space Fish by Guest Author: Justin Armstrong

“We move so fast now, new things can only be new for a few moments. The special starts to rub off and the sharp edges that make them unique are filed smooth the instant we begin to explain and define them. “

Photo by Jonathan Kelley

“What if there were space fish?”

“You mean fish that swim around in space?”

“Yeah, they would swim around amongst the planets and stars. In the space currents.”

“That’s very interesting. But there aren’t currents in space, there isn’t anything. Space fish would have a propulsion problem.”

“Oh. Because space, it’s like, a vacuum?”

“Right, moving their tails and fins wouldn’t cause them to move, they couldn’t move themselves.”

“They would need jets or something.”

“Or something.”

[from hank’s sketchbook]

In short order, JK banjaxed my dreams of Space Fish. I pointed my eyes back to the window into the night sky framed by sycamore branches, and in the center of this hole in the forest canopy was a constellation whose name I didn’t know.

I reminded myself that it wouldn’t matter even if Space Fish were real. Because things that are spectacular can only remain spectacular for a few moments. If a scientist found a pod of Space Fish it would be headline news for an entire day, maybe even two. But then Space Fish would be in the clutches of the internet, the internet that introduces new information and immediately begins churning it inside the content cycle. As it iterates it mutates that information, spinning it on itself until it becomes a parody of what it was when it began. This takes moments. Within days of their discovery, Space Fish would be memefied. Twitter would start in awe but then slowly start to mock. Then Space Fish would somehow become an oddly partisan issue. Within a week there would be BuzzFeed quizzes: “What Type of Space Fish are You? (Number 7s, you know who you are!)”.

It wouldn’t matter if Space Fish were real, because the most spectacular things become homogenized at light speed once they are discovered. We move so fast now, new things can only be new for a few moments. The special starts to rub off and the sharp edges that make them unique are filed smooth the instant we begin to explain and define them. We have to explain them. We want to understand them. And we want others to know that we understand. The thing that defied the norms we created now fits concisely in our pocket.

I found Space Fish in the corner of two states, where the small towns are still set in the 1980s, and the tacos are pretty good. They’ve been sitting out there this whole time and no one raised their hand to let others know they found them. As anglers, we bemoan the “now”. We lust with nostalgia for yesteryear, for less pressure, for solitude in unsullied fisheries. We lust for something that hasn’t been “found” yet. We’re looking for that place that progress forgot to include, that place that was either undiscovered or visited only by those who knew to keep their mouths shut.

Which is why I can’t tell you about Space Fish. The Space Fish can only remain special if I find them and don’t tell anyone. I can’t allow anyone the opportunity to colonize and adulterate them, to make them part of the human universe. So I’m not going to tell you about Space Fish.

-Justin Armstrong

Trip Reports: Vol. 1

“When the ripples had dissipated, a trap door opened, and the angelic white Boogle Bug was flushed into the netherworld. We found Bart.”

The following is a joint retelling of our recent canoe trip in Upstate South Carolina. Our words are woven together into one narrative, each author’s voice following his initials.

J (Jonathan Kelley):

“Why do you want to go and mess around with that f****** river?”

“Because it’s there.”

Besides the awe-inspiring cinematography and scenery in the movie Deliverance, that quote is what stuck out to me the most. I’ve messed around on the Chattooga before. I’ve waded around in some of the trout sections and watched guided rafts plunge over Bull Sluice. With a long weekend coming up, and the heat index climbing, Hank and I planned to try a proper overnighter on a quieter section, hoping for cool mountain air, and a chance to find Bart.

H (Hank):

With my 1979 Blue Hole canoe strapped down tight, “Yep she ain’t goin’ nowhere”, I set off from Auburn a few minutes after Jonathan got on the interstate in Birmingham. I felt nervous about the trip, not because of any movie I wish I could unsee, but because I had done the absolute bare minimum amount of planning to get us home safe. Nonetheless, I trusted the intel I got from some upstate Tigers, and I was excited to test my limits as a backcountry canoeist.

J:

After driving through a flooded creek to reach the take out point we shuttled about 12 miles upstream and put in. We saw several baby Bartram’s bass right at the put in and we both smiled without having to say more. It was going to be a good trip. We launched and quietly floated through the crystalline waters, spotting trout, sunfish, and suckers cruising along the sparkling mica river bottom. Before long, we got to a shady spot with some still water and downed wood.

All photos but this one by Jonathan Kelley

H:

I said “toss one way up in there.” With a quick check for back-cast clearance, Jonathan slung a popper uncomfortably far over some submerged timber. When the ripples had dissipated, a trap door opened, and the angelic white Boogle Bug was flushed into the netherworld. We found Bart. “Mission accomplished. Let’s go home,” we joked, knowing we had at least 24 hours to cover the 10 miles down to the 4Runner.

J:

As the daylight waned we caught more native bass, some rainbow trout and gorgeous redbreast sunfish. We exclaimed at their fire-and-ice hotrod markings. A few more toilet bowl slurps and a crushing eat in a deep tail out produced a handful of “trophy” Barts. As we cruised to the golden sandy beach where we had planned to camp on Google maps, we both laughed again. One of the prettiest camp spots we’ve ever seen. We pitched the tent and Oggie, Hank’s young chocolate lab, ran around the beach, freed from the confines of his Royalex jail cell. I took a dip in a little side branch with a sandy bottom I dubbed “the spa”.

H:

While Jonathan soaked, I poured Oggie’s daily ration into the bottom of the canoe. Like a few other sort of important items, I forgot his bowl in my absolute mess of a car. As the sky darkened, we watched trout leap from the riffle in front of us. We finished the whisky a little too quickly and called it early on account of wet firewood. I don’t know if Oggie’s savage dream-kicking or the light from the moon was to blame for my lack of sleep, but I didn’t care. I was just grateful to be exactly where I belong.

J:

The next morning, we knew there were going to be a few treacherous areas to get through. With every run through a chute, our teamwork improved, and our confidence increased. We hollered at the bottom of even the easiest rapids. But, near the end of the afternoon, we turned a corner and came down to a long slot canyon with a lot of white water. “Are we gonna go for it?” Hank asked. Without much hesitation I said, “Let’s do it”. Hank muttered, “Well this might be the one”, and we stifled nervous laughter.

H:

We should have just pulled over and scouted it. We didn’t even think about it. We didn’t even pause to put our life jackets on properly. I tried to line up the bow so we wouldn’t go in sideways, but almost as soon as I thought “We might pull this off!”, Oggie lost his footing, and the boat rocked. We braced against the gunwales, and suddenly the utility of our paddles evaporated. Even if we knew what they were for, all hope of using them properly was now lost.

J:

We hit the chute and midway down started rolling to the right. Everything went black for a few seconds and when I peered up out of the chilly water, I saw the canoe overturned, but nobody else. I thought, “How am I going to get Hank out from underneath there when I can’t touch the bottom and we’re flying down this rapid?”

H:

Blind with adrenaline, I snatched the bag with my keys and phone and tried with my other hand to hold onto the canoe and find my footing on the river bottom. I got pulled under and bounced off of every rock in that rapid before I could even take a breath. I kicked desperately in my ratty Chacos trying to keep the canoe from dragging me down, but I realized I was sinking the boat as much as it was sinking me, so I let it go and came up for air. Thank you, Jesus.

J:

After another minute or so bobbing down the tail-out we were able drag our dry bags to shore and drift into a beach. As we collected our scattered flotsam, relief started to cool the adrenaline. We both knew we were very lucky to be alive although those words were not said. The gear in my 2 failed dry bags, and both of our fly rods were not so lucky. We cheesed for a selfie.

H:

Oggie seemed to know that what had just happened was not part of the plan. He seemed a little rattled, and definitely reluctant to get back in the boat. But we had another two miles to cover, and we hadn’t even got to the worst rapids yet. Needless to say, we portaged over the rest of them, stopping to admire the Jurassic (Mesozoic?) rock formations that just barely make Deliverance worth watching. Not sure if it was the adrenaline high, or a change in the lighting, but suddenly the rhododendrons became twice as beautiful.

J:

During the long and complicated portage, I slipped about half a dozen times, wading boots be damned. Both of our legs got beat up pretty badly. As we approached the take-out we heard faint music that became louder: reggaetón, not banjos. There was a beach party going on and to our surprise, the friendly locals helped us bring our gear back up to the 4Runner. Some funny looks were given to us by helmet wearing whitewater kayakers that launched downstream from us. We cracked some beers and thanked Mother Chattooga for her mercy.

H:

After our trip, I watched YouTube videos of people running the rapid we flipped at. It looked about as dangerous as a kiddy pool waterslide. My ego whimpered, but that was all it took for us to learn our lesson, and we won’t be so casual about life jackets again. The danger of the rapids kind of added a secret ingredient to our trip. Just enough trauma to bond over, but not enough to scare us off rivers for good. Hell, we were back on another river the next day, strapped up tight, and happy to be still allowed to receive the gifts of flowing water.

On healing {Part Two} by Guest Author: Hugh Cheek

“When I can step back and look, I find peace. When I can remember to receive, I can be filled with more than I can take in.”

I can remember one of the first moments in life I felt unsafe. As an 8-year-old boy, I was climbing a beautiful, tall magnolia in my friend’s grandmother’s backyard. About fifteen to twenty feet into my joyful boyhood conquering, sweet magnolia let go of her limb beneath my feet. I remember hitting several other of her branches as she brought me to a sudden stop at her roots. Immediately standing up, I knew something was not right with my wrist. I felt numb, scared.

A new sensation of fear and loneliness came over me. There was no parent to run to or place of comfort. It was not obviously deformed, but if you have ever broken something, you just know it’s broke. One minute you’re a child at play and free, the next minute you’re wounded and alone. A lesson I now only look back on to realize, that same boy still longs to play, but has a deeper wound. One you can’t autograph or club anyone with. A wound no one wants.

On April 24th, 2013, my wife, Morgan, and I were graced with the beautiful gift of twin girls. Gorgeous like their mother with beaming smiles. Serious, at times, like their father. Ally or “Algae” was feisty and full of strength like Morgan, Bailey Grace or “B Jop,” was reserved and relaxed like her daddy (most of the time). These two beauties rode two thrones. One of hot pink, and the other of royal purple. To attempt now to write more about these two would be a cheap offering as this post is less about their life and more about the gaping void without them. There are not enough words on these pages to describe their angelic, pure vibrance.

On July 13th, 2019 and December 16th, 2020, they both respectively returned to the dust from which they came. Worse than a cruel branch snapping beneath your feet, closer to castration and a heart removal. You shouldn’t survive that, but you’re left to. There is something about the four-month point after trauma/death for me. On both occasions, I melted into a shell of myself. Constant nausea, abdominal pain, dizzy, downright mentally unstable. I found myself figuratively dragging myself between patient rooms, feeling like I was pulling myself through boggy soil and manure. Not suicidal, by Grace alone, but wondering if I would be able to hang on.

What happens when the irrational takes over the rational? When down is up and up is nowhere in sight. What do you do when you are very much alive, but dying? Others see you standing, but the internal wound is gushing, crushing. You white knuckle the steering wheel going 75 and scream as loud as you can to see if anyone passing can hear you. What the hell do you do when all is done?

a PLACE of healing

Some call it river therapy, some go for escape. I just call it a PLACE. A place to be present, a place to feel grounded and connected again. We are all drawn to the water. I find it interesting that patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder are often very attracted to water. We have a lot to learn from those with “disabilities” about each of our true “abilities.” Something within our very core longs to sit and gaze at the rushing water and crashing waves. A baptism of balm for worn out and thirsty souls.

“And I heard a sound FROM HEAVEN like the roar of rushing waters and like a loud peal of thunder. The sound I heard was like that of harpists playing their harps.” Revelation 14:2.

Is it a stretch for the music of heaven to be like the house of healing in Minas Tirith from Tolkien’s tales? A place for wounded soldiers to be tended to. Tended to by something larger than ourselves, but for ourselves. The water and fly fishing have been something of the sorts for me.

I used to go to the river, frantically looking at my watch to see how much time I had left. Trying to exhaustion to catch, to fill my soul with something. In the Spring of 2019, standing in the shoals of the Coosa River, something changed. I realized that I was not there to take or achieve anything, but simply to receive. I had become so focused on efficiency, that I missed the intimacy. A call to come and rest. Receive creation as what it is. A surprising gift that I enjoy more when I have less expectation.

Or maybe now, I have expectation of receiving instead of my own twisted version of what it should look like or be like. I still have moments when I am so hyper focused on the hunt for a fish, that I miss the kingfisher, fly catcher, moon flower of grace waiting for me there. When I can step back and look, I find peace. When I can remember to receive, I can be filled with more than I can take in. An abundance of sorts. A feeding frenzy for the soul. I picture myself in bed in that “house of healing” there, with Jesus and Strider gently dabbing my wounds.

I apologize if any of this is confusing to this point, but my hope is that you see a window into a heart of a man, who is hurting but healing. Who is struggling, but not without hope. The following are a series of events and writings (poetry?) over the last 6 months, that illustrate what I am speaking of above. A few places where I have found presence and rest. I hope it somehow encourages you.

“Nothing is given that will not be taken, nothing is taken that was not first given.”

A few words of final advice to my co-sufferer. “Don’t sweat the small stuff” is horse shit. Worry less about the big stuff, enjoy more of the small stuff for what they really are. Moments, glimpses into peace, beauty, rest. Efficiency is the enemy of intimacy. Take time to heal, be patient with yourself. Show up with less expectation and receive what is already there for you. RECEIVE what is given. Rest in the receiving. Take time to be present in your recreation. Be distracted less and present more. Read good books and listen.

Step off the battlefield and allow someone else to look at your wound beneath the bandage. Reveal these to someone else who has suffered much and been trained (either professionally or through life seasoning) to be a SAFE listener. Take risks and love even with the facts suggest otherwise.

On homecoming, by Guest Author: Jonathan Kelley

“Much more of my time fishing has been rooted in the old ways and that is something I now give myself permission to take pride in.”

James Lewis Goggins, photographed at his home in Brierfield, AL by his grandson Jonathan Kelley 2021.

I’m 38 and my Paw is 83. Like some astronomical phenomenon, our ages mirror each other every 11 years. Taking notice of this cycle of symmetry made me realize how no matter where life takes me, I always return back to my center when I’m with Paw on the river. I had an epiphany last year while we were fishing together about how this synchronicity has revealed itself in my life as an angler, which of course began under his instruction.

My Paw grew up in mining camps around the Cahaba River in the years following the Great Depression. His family hunted and fished for all of their meat, and that way of life never wore off. During his 40 years at O’Neal Steel in Birmingham, he would drive back to the country where he was raised every weekend. He leased paper company land and built a small rustic cabin, “The Shack”, overlooking Half Mile Shoals on the lower Cahaba River. His crew would run trot lines and fish at night, cooking their catch on the campfire. Although I always respected his old country ways, I grew to think there should be more to fishing than just coming home with a heavy stringer. My epiphany made me realize that isn’t really the case.

When I was in grade-school, Paw always had me by his side and gave calm instruction on whatever I needed to be learning. Oftentimes, a fishing pole was the main subject. My anticipation would build all week and when the school bell rang at 3pm on some Fridays, Paw would be waiting outside in his little brown Mazda pickup. When we arrived at the river, he would show me how to flip rocks to find salamanders, crawdads and hellgrammites. We would seine the river and throw minnow baskets in the “branches” that fed the river to catch chub minnows to bait trotlines. These were the old country ways; proven techniques to assure the success of a catch and filling your family’s bellies. With the bait we caught, we would float down the Cahaba in a flat bottomed boat and a few 14 foot cane “dobbing” poles. Using a stealthy turkey quill indicator above Catawba worms (aka “catfish candy”) was his preferred technique to trick skittish catfish. The excitement of not knowing what would pull down the quill became what I dreamed about throughout the week. Crickets, hellgrammites and worms triggered eats from bluegill, redeye and spotted bass.

After a heart bypass surgery, and a partial removal of his colon, my Paw retired at age 58. He and my Granny built a house in Brierfield, AL with a 1 acre pond loaded with largemouth bass and bluegill, and I evolved into a new kind of angler. Every summer for the next five years I spent on their 25 acres, but watching bobbers didn’t cut it for me anymore so I started conventional fishing and targeting big bass like I saw on TV. Paw was supportive of me but he stuck to casting red worms for bedding bluegill from the other side of the boat.

When I got to college, I evolved yet again into a fly fisherman. I mostly taught myself, but I got the inspiration from old Field and Stream magazines in Paw’s shop. Incredibly beautiful scenes from the West with big mountains and anglers casting fly rods grabbed my attention. I bought my first fly rod, a White River 9 Foot 5 weight for 50 dollars. After graduation, I had the opportunity to move west to Bend, Oregon and live out the scenes from the magazines I had grown to adore. Torn about leaving family and tradition behind, my Paw encouraged me to go live my dream.

Fly fishing became an obsession for me thanks to Deschutes River redband trout, and summer steelhead. Paw’s teachings in country entomology proved useful as I learned to mimic all the insect hatches out west. I made lifelong friends on the River, and loved every minute I spent in that cool flowing water. Maybe I wouldn’t be such a passionate angler if it weren’t for my time in Oregon. But, coming home to my roots has helped me see what I was angling for in the first place.

“The Shack” memorialized in oil paint by Silvia Manning, displayed with mounted buck deer taken in Bibb County.

After almost 6 years away from home, I finally returned to the little Cahaba in Bibb County with Paw. He with his Zebco 33 and me with my 3 weight. For the next several years every time we fished together he did his thing and I did mine. He would bait and catch a stringer full for fish fries with his friends. I would use my fly rod and handle the fish with care before release. I remember thinking to myself that I had moved beyond the need to use an easy method and fill a stringer. How could he still enjoy throwing out a piece of bait and waiting for something to eat it? Why was the focus always on catching fish to eat? Why hadn’t he “evolved” like me?

Last Easter I finally understood. We headed to the river. He brought his grocery sack of chicken livers, red worms, some gold hooks and split shot. I had my 4 weight, hip pack, camera and some flies ready for one of our normal “separate but together” outings. The water was high from recent rains. We went to a steep wooded bank with no room to cast my fly rod. It had been years since the last time I baited a hook. I thought “Aw, what the hell?” and sliced a chicken liver and threaded it on one of the long shanked gold hooks.

We both cast out and sat in silence for a few minutes. I noticed him to be content and sitting in complete stillness, just like I love to do. Before long he had a catfish bending his rod. He reeled it in and I helped him land it since his arthritis kept him seated most of the time. We both recast and after a couple minutes we were doubled up! Laughter echoed off the limestone cliffs as we reeled in some beautiful blue cats together. “These are great eatin size” he said. The rest of the day was filled with more of the same, and I was overjoyed.

I gave Paw a hug, we headed back to his house and cleaned the fish together. As always, he encouraged me to take some of the fish home and cook them. Every previous time I had said no thanks, but this time was different. I realized that eating the day's catch was important to Paw. I drove back to my home in the city and cooked catfish and grits for my wife Anna. As I thought more about the day it became obvious that the method of fishing is not important. Every person has their own values and reasons for being on the water. Much more of my time fishing has been rooted in the old ways and that is something I now give myself permission to take pride in. Not focusing on fly fishing that day allowed me to be present in the moment and enjoy time with Paw. I began to understand that the movement of the river made me feel still and content just like him. I’m eternally grateful for what he has taught me and still learn from the river every time I listen. I acknowledge that my experiences have made me into a different angler than the one Paw had so graciously trained, but also that I am still the turkey-quill kid in my heart, and the river is my centering place thanks to him.

Paw, seated on the banks of the little Cahaba River, Zebco in hand.

On healing {Part One}

There is no turn-key solution to suffering, but hopefully by sharing this series of posts, anyone can find something they can relate to.

photo by Jonathan Kelley

Recently I posted on my Instagram page about how far I’ve come since my dark days last year. It became quickly evident that a lot of you have gone or are currently going through similar struggles. I wanted to use this long form blog post to expand upon a few of the points that we discussed, both publicly and privately. Also, I wanted to set the stage for a series of posts on this subject by a few different authors. There is no turn-key solution to suffering, but hopefully by sharing our stories, anyone can find something they can relate to.

In my post, I mentioned how difficult it was for me to “get myself off the couch” when I was really in my worst times. I meant that I was literally unable to stand up and do easy tasks like tidy up the living room or wash dishes. A few of you talked about your own metaphorical “couch”: something that sucks out your marrow and leaves you paralyzed.

For some, it was grief, feeling unable to get away from the pain of loss. For others, it was family conflict and stress from work. I think a lot of you know the feeling of being trapped and exhausted by a problem or situation, unable to muster the energy to do things that normally make you feel better, like getting outdoors.

Even if you haven’t been depressed, you have surely felt the restorative powers of a walk in the woods, or a soak in the creek. But an important thing to understand for we who need healing are the limits of those powers, otherwise we may just be slapping band-aids on bullet holes. For a while, I used “river therapy” to soothe my soul, but I eventually realized that no amount of dopamine-laced hook-setting was going to fill my creel. My problems always followed me back to the trailhead and all the way back home. Over the course of about 7 months, I did three things that helped me get the monkey off my back. I went deeper into nature, opened up to my loved ones, and talked to a professional.

I read books and poetry and learned about ritualizing my interactions with nature. I tried to foster a sense of gratitude for the things that made me feel whole. Like I said in my post On Placeness, I leaned on my senses and chased that feeling of being known. I highly recommend Wendell Berry’s poems, and “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall-Kimmerer, if this kind of thing interests you. Hopefully you have enough energy to give it a shot, but if you don’t, there are other options.

I think my relationship with nature is what kept me from hitting rock bottom when nobody knew how I was feeling. I felt so alone last year. I didn’t think I was worth anybody’s time. When my loved ones realized that I was not taking care of myself anymore, they brought me in close, and I opened up to them. If you don’t have anyone to open up to, I’m here listening. I’m hoping that my Instagram post showed you that you aren’t alone, and that you can leverage strength from this community of outdoorsmen.

If you don’t have the energy for going deeper into nature, or you feel that opening up is too complicated, that’s okay. I think talking to a professional should be your priority. Seeking help is not giving up. It’s the opposite. It’s taking a big brave step towards being your best self. Shouldering your problems on your own sounds like the honorable thing to do, but I heard a hilarious spoof of that macho attitude the other day on Instagram: “Don’t let anybody ruin your day. Be a man and ruin it yourself.” I don’t want it to sound like I’m preaching on “toxic masculinity”. I’m not here on behalf of woke-ism. I’m here because I feel better, and I want you to, too.

Photo by Jonathan Kelley

On participation, by Guest Author: Alexandra McNeal

“I was no longer just an onlooker, but a participant in that ecosystem.”

I think I have always been drawn to the idea of the land providing for me. From a young age I had an obsession with survivor stories (think Robinson Crusoe, The Hatchet, My Side of the Mountain, etc.) where people figured out how to subsist on what was available to them. My friends and I would play act our own versions of these stories in the woods: building shelters and attempting to start fires. I remember specifically a time we managed to catch a crawfish on the banks of the Satilla River, and we were so proud of our prize we cooked it over a fire in an old, empty SpaghettiOs can.

Reveling in our bounty on the riverbank we thought, “We could totally make it out here”

Most of my life this interest was more lighthearted, but lately I have had the increasing desire to truly attempt to live “closer to the ground” - a phrase borrowed from Dylan Tomine’s book that’s played a part in rekindling this passion. The way he writes about foraging mushrooms and digging for geoduck clams will make you instantly want to go outside and learn how your land can feed you. The result has been a deeper connection forged between me and the landscape via growing, foraging, and harvesting what I can or sourcing locally the foods that I can’t. It’s far from perfect (trust me, we order plenty of take out) but the pursuit of it is deeply fulfilling to me.

I love growing vegetables in our small garden and tracking the seasons to know when I should hunt chanterelles or check my persimmon trees; however, successfully hunting an animal (aside from the occasional fish) was something I had yet to achieve. As someone who includes meat on their plate, I felt it was something I needed to experience to fully appreciate where my food was coming from and to understand the gravity of my choices at the grocery store.

Over the last few years, I tagged along on rabbit, squirrel, and turkey hunts with my husband, sat in deer stands, and truly enjoyed helping him process his successful deer harvests. I was getting closer little by little but all that time I was still just an observer reaping the rewards of someone else’s hunting success. Truthfully, I was dragging my feet and not making it happen because I was nervous. The decision to take a life seemed like a heavy burden and I wasn’t sure if I was ready to shoulder the potential consequences. What if I made a bad shot? What if I caused something undue suffering?

Of all the hunts I’ve gotten to be a part of I felt that turkey hunting suited me best. There is a rhythm to it I enjoy. Walk a while. Listen a while. Sit and wait and watch a while. It’s a nice cadence that allows you to enjoy much more than just the task at hand.

A year ago, I was present when my husband and a friend successfully killed a beautiful tom on our Satilla River property, a piece of land my family has part owned for almost 2 decades. To bear witness to that and know all that went into achieving it made me want that experience for myself.

Fast forward to this turkey season and I’m back in South Georgia, but this time with a gun and intentions.

We set out early, around 6:20 am, and I revel in our pre-dawn walk through the woods. I love this part of the hunt; something about being in the woods at this hour makes you feel exquisitely alive. The only sounds are a chuck-will’s-widow singing his final set before first light, the swishing sound of our boots on the soft sandy road, and the occasional distant droning of a train. Dark pines tower over us - silhouetted against the fading stars.

We find a place to stop and listen for a while. It’s amazing the contrast of sounds you’ll hear in just a 20-minute span of time. As our chuck-will’s-widow finishes his solo, we have a brief intermission before our diurnal avian friends begin. It starts out slow at first. One or two brave birds tentatively break the silence (why do I feel like it’s always a cardinal??) That seems to signal the rest of the choir to start up and within minutes it’s utter cacophony. I close my eyes, leaning my head back, trying to parse a very different call from the chatter.

Maybe a half-hour goes by and we finally hear a gobble echo through the trees. My heart skips a beat or two. The tom doesn’t seem far so we quickly set up our decoy, or “Winona” as our friend lovingly calls her, and get situated against a tree. I’m trying to compose myself and get prepared - going over in my head everything we had talked about shot placement. After about 45 min my heart rate had calmed, my hands were numb from the cold, and it seemed this bird wasn’t going to play. My friend gave one final call that was met with a silence we took personally.

My husband was hunting a different part of the property, but he had texted that he wasn’t hearing much so we set off to check out another spot. It's about 8 am at this point and the sunlight is streaming through the pine trees as we walk and call our way down a trail. I think I hear a gobble over my friend’s mouth call but I’m not sure. He calls one more time and we get an instant response, closer this time.

Again, we hurry to get set up against a good tree. My friend and the bird have a nice call and response going on, so we can hear him getting closer and closer. My heart is racing so fast. I do some box breathing to try and steady myself. I take the safety off and I am laser focused. My breath under control, I feel calm and ready but I also vaguely notice my knee is shaking uncontrollably. Hmm. I don’t think it’s just from the cold. Also, why is my mouth so dry?

I truly cannot say how much time passed in these moments. It could have been 5 minutes. It could have been 20. I am aimed exactly where we think the bird will come out. We see something through the bushes – not one, but two dark shapes moving towards us! Of course, they decide to come around to our left side, so we quickly have to shift so I can swing my legs around for my gun to rest on. Hurriedly, my friend tells me when they come from behind that pine, they’ll be about 25 yards and I’ll need to take the first shot I get. Otherwise, they will see us before they see Winona.

The butt of the gun is braced hard against my shoulder. Both turkeys come barreling around the pine tree, unable to resist one last call. All I see is the bright red of the turkey’s neck, and I instantly pull the trigger, aiming where the plumage meets the skin. The shot jolts me back and I blink… but see nothing in front of me but empty woods. I hear a rapid scampering away through the trees.

I missed.

I heaved a giant sigh and may have uttered an expletive or two.

I got up and walked back and forth between the trees and where I took my shot from, checking the trunks and looking for any sign of where I might have missed but found nothing. I truly could not believe I missed – I felt so sure about my shot! But there was no sign I had hit the bird at all, not even a feather out of place. Maybe my shaking was worse than I realized? I felt sick to think I may have injured the bird, but my friend said he watched it run off perfectly fine.

We walk back out to the dirt road and I see my husband way in the distance, speed walking down through the sand to us. While we wait for him, we both hear a faint rustling out in the woods and look at each other questioningly. We keep listening and hear nothing. My husband gets to us, breathing heavily.

“I started running when I heard the shot!”

I was so embarrassed and disappointed to tell him I had missed.

We start to check our maps to make a new game plan but I could not shake the feeling that I had injured this bird. We decided to fan out and check the area again.

A few minutes into our search I hear my friend whistle off to my right.

“Alexandra, I think you need to get over here!”

I am running before he finishes speaking and a few seconds later I can see a bird on the ground at his feet. My bird! More expletives (of a decidedly different tone) were uttered.

I quite literally fall to my knees next to the tom, hands against my face in utter disbelief. He is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen. He is pristine and I sit in awe of him for a long time. I cannot stop stroking his feathers and marveling at his iridescence. My eyes fill with tears; I am choked up but also so happy. Honestly, happier than I thought I would be in this moment and overwhelmingly thankful. Thankful for this bird and his life. Thankful for my husband and friend who helped prepare me and make this moment happen. Thankful that we decided to check one last time.

I don’t know if other hunters feel the way I feel now, after taking their first animal. Maybe I’m a bit more sensitive and introspective than most; but I feel like my relationship with the land changed in that moment. I was no longer just an onlooker, but a participant in that ecosystem.

I initially wanted this experience to take part in the procurement of the protein I eat, but I won’t lie that I feel like I have reasons beyond that to pursue turkeys and other wild game in the future. To look at the landscape through the lens of a hunter adds a new dimension to the outdoors experience. It is an exceptionally grounding feeling. The absolute thrill of hearing that turkey gobble – especially when it’s responding to YOU. That’s a feeling and a connection you can’t bottle. To top it all off, these pursuits allow you to truly step away from the world and simply exist in the moment. A day in the forest spent sitting, listening, thinking, observing…. I think most people could benefit from a day like that.

I understand that I’m exceedingly fortunate my first time hunting a turkey was successful. That’s what having excellent hunting mentors will do for you and I am truly grateful for them. I also understand that in the future, the turkey will likely best me 99% of the time and, luckily for us both, I am perfectly content with that.

That very night we thin sliced and cooked hot on the grill one of the breasts from the tom; it was simple and delicious. I’d like to think the girl eating her crawfish out of a SpaghettiOs can would be proud.

Alexandra Nicole McNeal is a biologist turned wildlife artist as well as an avid angler and a lover of all things outdoors. She paints the subjects she is most connected with- feathers, shells, flora, and fauna with a strong nod to the Georgia coast where she grew up. You can follow and view her art @artbyalexandranicole on Instagram or at www.artbyalexandranicole.com

Photos provided by Clint McNeal and Swanny Evans.

On the hunstman’s ethos

A reflection on last winter’s deer season, and conscientious harvest.

This past deer season I was present for the harvest of three white tail deer: each with its own lessons that I’ve incorporated into my hunting ethos.

The first deer I ever shot was on the day before Thanksgiving, 2021. I was in Oak Bowery, Ala., with a good friend and mentor sitting in his shooting house on a power line. We watched as a few fawns and spikes milled around in the food plot and a large doe made her way out of the wood line. I lined up my shot behind the doe’s shoulder with a borrowed .270 and pulled the trigger.

CLICK.

I had forgotten to rack a round. My buddy took the rifle and quietly racked a round for me. “Don’t panic” he whispered. I lined up the shot again.

CLICK.

A dud. The first he or I had ever seen. This time, I changed out the round myself while the doe stared me down, and I dropped her with a “perfect shot.” Flabbergasted, we climbed down the ladder to collect her, and found a few quartz points that had been disced up by a tractor from the ground where she lay. Despite my blunders, which were partially out of my control, I was proud of the shot I made. So proud, that I didn’t mind the three-legged squirrel dog violently yanking on the doe’s hanging cape while I was quartering it at the farm house. “Sorry Hank, it’s tradition.”

The second deer was taken in Tuskegee National Forest. My good buddy had put in hours of scouting and sitting over two seasons to earn his first public land buck. Countless disheartening days of still woods, and being surrounded by scrapes and rubs in ghostly quiet woods had slightly worn the edges off his confidence. But on the morning of January 10th, he was rewarded, and I was witness.